State Space Form: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 91: | Line 91: | ||

\end{bmatrix}</math><br> | \end{bmatrix}</math><br> | ||

So then, since <math>Vin</math> is our forcing function <math>f</math>:<br> | So then, since <math>Vin</math> is our forcing function <math>f</math>:<br> | ||

<math>\mathbf{A}= | <math>\mathbf{A}=-\frac{R}{L} | ||

\begin{bmatrix} | \begin{bmatrix} | ||

1 & 1 \\ | 1 & 1 \\ | ||

1& 2 \\ | 1& 2 \\ | ||

\end{bmatrix}</math> | \end{bmatrix}</math> | ||

,<math>\mathbf{B}= | ,<math>\mathbf{B}=\frac{1}{L} | ||

\begin{bmatrix} | \begin{bmatrix} | ||

1 \\ | 1 \\ | ||

Revision as of 14:50, 7 March 2011

In my Signals and Systems II class at University of Idaho, we are learning about the state space form of representing a solution to a LTI differential equation. I'll add more here soon.

Consider the differential equation

or

The state of this equation can be described using what is called state space form. State space form gives the blah blah more here.

let

let

so

We can now re-write the equation above to be:

so

and from the definition above

We can take this and put it into matrix form:

Or, more generally,

This is called the state space representation of the differential equation. This can be quite useful because the entire description of the differential equation is available in the matrix, and is easily manipulated using linear algebra.

-Example-

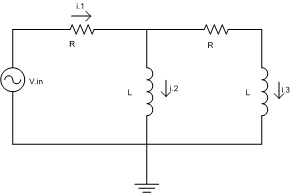

For the circuit below, find a set of state variable equations (there are several ways to do this, I will choose the one I feel is most intuitive.)

Start by using loop (also known as mesh or KVL) analysis.

Loop 1:

Loop 2:

Lets let:

and

So, . Substituting into the equations above, we get:

and

Where is the derivative of .

Solving these equations for and We find:

and

Now we can write these equations in stat space matrix form:

Where

and

So then, since is our forcing function :

,

We now have our differential equations in state space form.

I'll be adding more on how to use state space form to solve these equations as I have time.